Moving forward, we’re delving into each Disney animated feature, arranged in timeline fashion. We’ve entered the era of Disney Renaissance, a period marked by the resurgence of the company’s initial talent and creativity, sparked by the theatrical influence of Howard Ashman from Broadway. Regrettably, he had already departed before this revival, leaving a void that is palpable.

1992’s Aladdin stands among Disney’s most impressive works, rivaling some of the greatest animated films ever made on screen.

To scrutinize an animation thoroughly, the critic should examine each aspect such as characters, storyline, songs, and visuals under a meticulous lens. No matter how minute, there may be imperfections that can be detected in these areas.

If audiences hadn’t recently watched THE LITTLE MERMAID (1989), some of the shortcomings in this movie might not have been noticed as easily.

The movie, while inspired by the “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” tale from THE ARABIAN NIGHTS ENTERTAINMENT, significantly varies from it, particularly in the scene where an African sorcerer deceives Aladdin’s wife with a swap of lamps. Unlike the original story, Disney’s version depicts Aladdin as a street kid and thief rather than an honest son of a poor tailor. The cave of wonders is present, but there’s no magic ring in this adaptation. Moreover, unlike the original story, the setting is not an ancient city in China; instead, it has been adjusted to better suit modern audiences.

This movie heavily draws inspiration from the 1940 English fantasy film “The Thief of Bagdad,” which introduced the concept of a magical Near Eastern fairyland in Hollywood. Various elements found within this story can be seen throughout, such as the wicked Grand Vizier, the eccentric Sultan enamored with clocks and toys, his stunning daughter, the flying carpet, the genie, and more. The villainous Grand Vizier is even named Jaffar in this version, and he orchestrates a plot to wed the princess.

In this film, similar to “The Thief of Bagdad,” the narrative begins with a storyteller in a bustling marketplace narrating the yarn in a flashback style. This time, instead of the traditional storyteller, we have a chatty vendor trying to peddle the very lamp that’s central to the plot. Interestingly, unlike in other tales where the storyteller concludes the story at the end, here there is no such ending scene. Instead, the story is framed without a final frame or conclusion.

The peddler’s voice is provided by Robin Williams, renowned for his roles as Mork from “Mork & Mindy” and the genie, with Disney giving him creative freedom to incorporate his improvisational, rapid-fire humor and various character impressions. Robin Williams’ energetic, humorous style pervades the movie. Those who don’t find the Genie’s anachronisms and absurdities amusing might not fully enjoy this film.

In a twist of events, the sinister advisor Jafar yearns for the enchanted lamp hidden within the mystical Cavern of Marvels, a place he fears to tread upon personally. Enter his sarcastic companion, the parrot Iago, whose vocal cords are masterfully manipulated by Gilbert Gottfried. This role seems tailor-made for him. The intricate dance between Jafar’s icy demeanor and Iago’s grumbling complaints, shifting between servitude and camaraderie, creates a captivating villainous duo that stands out in the annals of Disney storytelling.

In the Broadway showstopper “One Jump,” the character Aladdin is presented. He sings about stealing a loaf of bread to survive in this number. His humorous companion, Abu the monkey, is not only amusing but also proves to be an efficient sidekick. Abu, like Aladdin, is skilled at pickpocketing and unlocking locks. Unlike Iago, Abu does not verbally communicate, but he seems to speak through his suggestive monkey sounds.

In my opinion, as a movie reviewer, the opening scene of Aladdin is nothing short of brilliant. When our charming rogue finds himself fleeing from the relentless guards in a series of hilarious escapes, it’s not just action-packed – it gives us a glimpse into his resourceful and quick-witted nature. But what truly steals the show is when Aladdin stumbles upon two wide-eyed waifs rummaging through trash for scraps. In an unexpected moment of kindness, he selflessly hands over his stolen loaf to them, showing us a side of him that’s warm-hearted and compassionate. This scene does more than introduce our protagonist – it sets the stage for the emotional journey we’re about to embark on.

Typically, characters who are thieves may not initially seem appealing, yet audiences often root for the underdog, empathize with those forced into crime by circumstances, and can even forgive a thief if they steal from a more corrupt individual, like a criminal or a tyrant. In this narrative, the authors skillfully employ these common themes to make their rogue character appear noble at heart.

Later, it’s those very girls that Aladdin rescues from the cruel lashes of a haughty prince riding a proud horse, whose sharp words wound Aladdin far more profoundly than any lash could.

The rhymes in “One Jump” are somewhat awkward, not quite reaching the cleverness of Ashman, but it’s still an energetic and functional tune, one that easily sticks in your head. In a memorable recurrence, it also reveals key aspects about our main character, their personality, and their intentions.

A subtle technique often employed in a skillfully crafted musical is to express the main character’s deepest aspirations through the lyrics of his initial song, giving the audience insight into his life goals. The irony lies in two folds: while the song pleads for the world to peer deeper and understand him truly, he ends up hiding his identity in the second act of the movie.

In a different phrasing: Jasmin, the Sultan’s radiant daughter, feels discontented with her destiny, as she is expected to wed a prince according to tradition. However, she dreams of marrying for love instead. After an argument with her father, she flees the harem walls, eventually winding up in the bustling marketplace where only Aladdin’s urban cunning can save her from potential perils.

Love flourishes, and the movie subtly illustrates how these seemingly disparate individuals share unexpected similarities. This unity of feelings is beautifully encapsulated in a shared phrase they utter simultaneously, each taken aback to discover their sentiments mirrored.

As a movie enthusiast, I must confess that Disney has certainly created their share of enchanting princesses across numerous films. Yet, there’s something truly captivating about Princess Jasmine – her cascading raven tresses and sparkling eyes make her stand out. It seems the animators dedicated special attention to ensuring each harem girl was as charming as possible, much like how they crafted the attractive blonde village girls from the previous movie. This level of aesthetic detail, unfortunately, appears to be a design aspect that modern Disney has lost its zeal to replicate.

Eventually, by means of sorcery, Jafar uncovers that Aladdin is fated to explore the Awe-inspiring Cave of Wonders. Taking advantage of his position as Vizier and the Sultan’s ignorance and simplicity, he orchestrates Aladdin’s arrest. However, he also sets up a plan for Aladdin’s escape. Guided by Jafar, Aladdin finds himself in the Cave of Wonders, a sight that matches its grandiose name with its breathtaking beauty and mystery. The cavern is filled with gold, precious gems, and towering statues.

In this setting, we encounter the ingenious character known as the Flying Carpet from Disney, who skillfully embodies a lively persona without a face, voice, or traditional means of expression. Instead, it conveys emotions through a form of rug-acting.

In the cave, betrayed by Jafar and abandoned to perish, Aladdin discovers a lamp and summons its magical inhabitant – a genie who belts out the second standout number of the movie: “A Friend Like Me.” This song, devoid of awkward verses, showcases the genie’s incredible wit, if not his eccentricity, perfectly embodying Robin William’s portrayal.

Contrasting sharply with the malicious and derisive genie from THIEF OF BAGDAD, this genie is plump, friendly, and endearing instead. Disney introduces an original twist in this retelling of the story: the genie is bound to the lamp, serving as its slave, only able to gain freedom if his master chooses to set him free.

Initially, Aladdin desires to wed the princess, but since he’s not a prince, it’s against the law. Consequently, the genie creates elegant outfits for him, an elephant for transportation, potential suitors, and attendants, as well as another spectacular stage performance.

Yet, as Jasmine believed the marketplace boy had been killed by Jafar, and wary of suitors coveting her wealth and status, she rejects the pretender prince.

In an effort to keep up the lie after being told to be honest, Aladdin instead decides to whisk her away on a magical carpet journey, aiming to flee the monotony of palace life – a lifestyle she had previously expressed a deep yearning for.

A new masterpiece of a song unfurls, unfortunately tainted by some clumsy rhymes. Jasmine manages to see through his disguise, yet Aladdin continues his deceit, feeling the pang of guilt: he recognizes that he’s empty without the genie and so hesitates to set him free.

he understands that he’s powerless without the genie and thus refuses to release him.

Upon coming back, the lovers share a kiss goodbye. Jafar attempts to kill him, but Aladdin manages to elude him, faces off against the antagonist, unveils his wickedness to the puzzled sultan, and compels the sorcerer to flee – however, now Jafar knows Aladdin’s true identity, and orchestrates a plan to snatch the lamp from him. The genie is forced to serve Jafar. With absolute control in hand, Jafar degrades the sultan and the princess into humiliating servitude, and exiles Aladdin to a freezing death in the Arctic.

In a thrilling turn of events, Aladdin is rescued and brought back by the magical Flying Carpet. Moreover, he devises an incredibly cunning scheme that outsmarts the seemingly unbeatable villain, Jafar, in what might just be the most ingenious plot twist of any Disney movie ever made.

In the course of the movie, Aladdin yearns for respect, not wanting to be known as a mere street urchin. Only when it’s too late does he understand that he must demonstrate his own worth instead of relying on magic. Interestingly, Aladdin recognizes this same flaw in Jafar, and tests him by stating that Jafar is powerless without the genie, much like how Aladdin came to terms with his own insufficiency in the previous scene.

Jafar is vanquished and exiled, along with Iago, his partner in crime. The genie persuades Aladdin to wish himself a prince once more, so he can marry the princess. However, having learned from past experiences, Aladdin sets the genie free instead. In an unusual resolution, the sultan disregards the law and permits their engagement regardless. As if in a comedic finale, the genie gives a knowing wink to the camera before soaring away, singing and yodeling.

1. The characters in this Disney production stand out for their exceptional detail and drawing, and Aladdin’s character is particularly well-rounded compared to other male leads. His motivations are as relatable as those of Jasmine, the princess. The voice acting is superb, with Robin Williams bringing an eccentric flair to the genie that also conveys a yearning for freedom, adding depth to this nonhuman character. The monkey and carpet’s voiceless portrayals are charming, and the dynamic between Jafar and Iago adds a touch of quirkiness.

2. This Disney production boasts some of the most exquisitely drawn and detailed characters within its canon. Aladdin is more three-dimensional than many other male leads, and his motivations resonate with those of Princess Jasmine. The voice acting is excellent, with Robin Williams infusing the genie with a madcap personality that also conveys a longing for freedom, making this nonhuman character seem human. The silent performances by the monkey and the carpet are endearing, and the relationship between Jafar and Iago adds a unique twist.

In the Thief of Bagdad, the Sultan appears to be an overused trope, remaining consistent with his past characterization as a weak, absent father figure – a common theme also observed in numerous Disney productions, where mothers are noticeably absent.

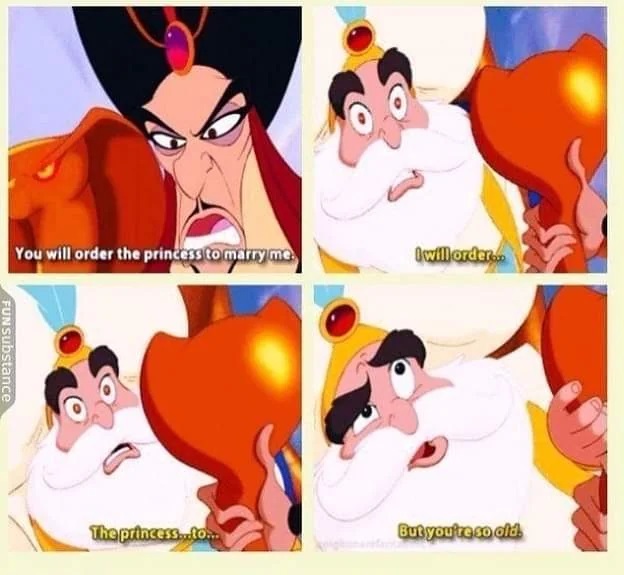

As a movie critic, I must admit that the voice acting and animation in this film have made the Sultan an irresistibly charming and amusing character. There’s no denying it – when Jafar, with his magic wand, tries to force a marriage between him and the princess, you can’t help but crack a smile as the little sultan, in all his chubbiness, looks up at the supposed groom-to-be and exclaims playfully, “But aren’t you just… so old?” It’s moments like these that make the film truly delightful.

In the style of Beauty and the Beast’s ballroom scene, there’s no noticeable digital computer work; instead, the carpet looks perfectly integrated with the traditional hand-drawn animation.

In the fictional city of Agrabah, reminiscent of Baghdad, stands a beautiful urban landscape filled with towering onion domes and slender minarets, all crafted in an enchanting, Arabic-inspired style. The artwork is remarkably detailed.

In this captivating tale designed for young audiences, I find the underlying message to be profoundly insightful: receiving what we desire holds no significance if our desires are misguided. Initially, Aladdin fell into this trap, while the villainous Jafar ultimately succumbed to it as well.

Jafar yearns for personal dominion and grandeur, ultimately ending up enslaved. Aladdin aspires to free his companion, sacrificing the wealth he was born into and enduring the film’s poignant solitude as he couldn’t marry his beloved, eventually receiving all that he gave up and even more.

Selfish wishes end in slavery. Selfless wishes grant more than was asked.

I pointed out minor issues, but it’s important to note that these would go unnoticed in a movie not compared to Disney’s top-tier productions. Some viewers might find Robin William’s genie character too excessive, and his frequent use of anachronisms could disrupt the immersive experience. Preferences vary.

Ashman’s unmatched talent is hard to replicate; other lyricists may not reach the same level of brilliance as him. However, that doesn’t mean their work is poor; it just might not be as exceptional.

In the third act, it appears that Aladdin’s redemption happens rather quickly. He genuinely tries to rectify his mistakes, but is cut off mid-apology, and subsequently becomes overpowered by the rapid succession of events.

In simpler terms, the main problem driving the storyline – that the princess needed to wed a prince – is dismissed at the end, which seems hasty and could have been resolved more elegantly. For instance, they could have made Aladdin a vizier or granted him a province, thereby making him a prince in his own right.

One minor, unnecessary issue that didn’t initially appear in the movie but has stuck with me since, is something I’d like to address later. This problem, though seemingly insignificant, has left an unpleasant impression on me.

In earlier times when home video technology was novel, the initial tune encountered criticism for political incorrectness upon its release on this platform. The lyrics of this opening song, which set the stage for the perils in the enchanting desert romance story inspired by Arabian Nights, originally contained content that raised concerns.

I hail from a distant land, a place that’s remote and vast,

Where nomadic camel caravans have a lasting cast.

There, they may sever your ear if you don’t meet their taste,

It’s an archaic practice, but, well, it’s the way of our past.

Casey Kasem, a well-known disc jockey, criticized a song’s depiction as criticism of Arabic brutality – this was indeed the intent of the lyrics. However, in an early instance of sensitivity outweighing art and truth, Disney revised the lyric to a vague phrase that didn’t match the rhythm, meaning, or theme.

Originally, I hail from a distant land with vast open plains,

Where herds of camel-drawn caravans freely roam.

The scorching heat is relentless, and it’s desolate, yet,

In its own unique way, it feels like home to me.

In this part of the song, the sudden shift in the singer’s voice might seem abrupt or jarring to the listener. It’s tricky when “intense” doesn’t rhyme with “face.” The rhythm also changes from a straightforward ABAB pattern to ABCBC, which requires an internal rhyme. This line, however, seems nonsensical because while mutilating ears is indeed barbaric, describing a hot climate as barbaric due to its vastness isn’t accurate.

In the movie, neither the arid landscape nor its heat are significant story elements, but the unkindness shown by merchants, guards, and high officials is a persistent theme. Despite this, Disney chose not to modify any scenes depicting children being menaced with a whip by a prince or a girl being punished for stealing by losing limbs, among other instances of Arabian harshness. These scenes remained unchanged. However, the humorous allusion to these events in the opening song was slightly altered.

Every time I watch the movie again, a nagging imperfection bothers me because the original version is unattainable for me. At this moment, a minuscule factor contributing to Disney’s eventual decline was set in motion. Admittedly, it’s just a tiny issue that detracts from an otherwise delightful film experience; however, the prick of this seemingly insignificant problem hits me right where it hurts.

Beyond some insignificant, picky-eyed imperfections, ALADDIN stands out as an undeniable classic. I couldn’t more enthusiastically endorse it. If by chance you’ve missed out on this masterpiece so far, consider yourself lucky – a world of marvels is about to unfold for you.

Read More

- Best Heavy Tanks in World of Tanks Blitz (2025)

- Stellar Blade New Update 1.012 on PS5 and PC Adds a Free Gift to All Gamers; Makes Hard Mode Easier to Access

- Here Are All of Taylor Swift’s Albums in Order of Release Date (2025 Update)

- [Guild War V32] Cultivation: Mortal to Immortal Codes (June 2025)

- [FARM COSMETICS] Roblox Grow a Garden Codes (May 2025)

- Criminal Justice Season 4 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- Death Stranding 2 smashes first game’s Metacritic score as one of 2025’s best games

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Beyoncé Flying Car Malfunction Incident at Houston Concert Explained

- Rachel Zegler Defends Her Bodyguard Danny Against Fan in Viral Clip

2025-04-14 03:31